By Marianna Grigoryan and Hasmik Hambardzumyan

30-years-old Anna had an abortion twice in the past year, one during the 14th week of the pregnancy and the other during the 13th. Both of her unborn children were boys, though the young woman “took them out” (a popular expression in Armenian for abortions) thinking they were girls.

“The ultrasound showed it was a girl, and as we already had two girls, my husband didn’t want one more, so we decided to take it out. I went to Yerevan, we took her out, and then the doctors came and told me it was a boy. It happened twice,” says Anna to MediaLab with deep regret, reluctant to accept what happened.

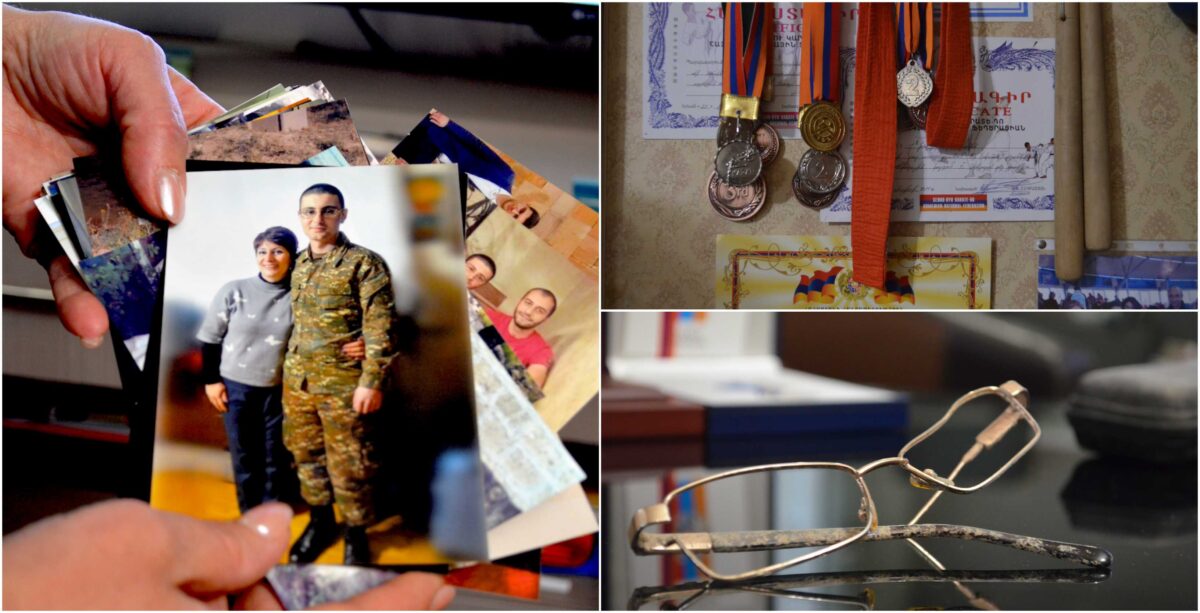

Anna holds the last picture of the fetus from the ultrasound scan in her hands, an already worn-out paper, the last remnant fact of her pregnancy. Every time she looks at the black-and-white photo, she starts to cry.

Anna is not the only one in Martuni town of Gegharkunik province who has taken the extreme step to have a son: sex-selective abortions continue here. Despite the extensive information campaigns against selective abortion in recent years, the issue of selective abortions in Armenia is still deeply disturbing, and, according to the experts, Gegharkunik province is a record holder in this regard.

Abortion in Armenia is legal on request up to 12 weeks of pregnancy. The amendments to the “Reproductive Health and Rights to Reproduction” law passed in 2016 banned abortions due to reasons other than on the list of clinical or social indications, including sex-selective abortions within 12-22 weeks of pregnancy. Illegal abortion is criminalized and carries a penalty ranging from a fine to imprisonment. However, given that the baby’s sex can only be identified after the 12 week of pregnancy, it becomes clear that what happens in this domain remains hidden and uncontrolled. Statistics in this field are incomplete: gender-based abortions in Armenia remain hidden behind closed doors.

The abortion surgery of 36-year-old Gayane (from Ijevan) at one of Yerevan medical facilities was performed the same way, secretly, lasting several hours. She says she paid 30,000 for the service, but everything was done without registration and protocol. Gayane says she had clearly decided to get rid of the baby girl. “Even if I die, I need to have one son for my husband.”

An experienced obstetrician-gynecologist, who preferred to remain anonymous, notes that to a great extent the laws in this sphere are not working. He also notes the great risk to women’s health, given that selective abortions are performed in the later period of pregnancy after the baby’s sex is revealed.

“As a person at the epicenter of the issue, I say that this law does not work. There will definitely be a doctor who will perform an abortion via an acquaintance or for extra money. There is no way to prove that abortion is sex-based. They say: ‘There was a developmental defect’. Well, it’s impossible to prove that it was not the case, or they simply hide the fact of abortion, how can you find out whether there was an abortion at all”, he says to MediaLab.

Gayane Avagyan, head of the Department of Mother and Child Healthcare at the Ministry of Healthcare, on the contrary, believes that since the adoption of the law in recent years, the situation has changed for the best and the birth rate of girls and boys has improved significantly.

Moreover, the official believes that banning sex-selective abortions after 13 weeks was a strict amendment.

“In 2014, we launched a project that would prohibit a woman from knowing the sex of her child before the 30th week of pregnancy. But all human rights organizations, as well as the Human Rights Defender, told us that we have no right to take such a step, as it violates the law on the right to get medical care – everyone has the right to information about herself and the fetus. Therefore, we were unable to take that step. This is the way chosen by India, where a woman who even tries to find out the sex of the child and doesn’t achieve any result, is subjected to a trial,” says Gayane Avagyan.

The average female-to-male ratio of children born in 2008-2012 was 100-115, in 2014 it was 100-113.4, in 2015 100-112.7, in 2016 100-111.9 and in 2017 100-109.8. According to the data released by the National Statistical Service, in 2018 the figure increased by one digit to 111 boys per 100 girls.

According to UN standards, the sex ratio of 105 boys per 100 girls without any intervention is considered normal.

“You know, going up or down by one digit is not serious statistics, we have seen such a high rate. It shows a decreasing tendency,” says Gayane Avagyan.

Unlike the specialist of the ministry who highlights positive dynamics, disturbing trends are noticed in the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA).

Since 1999 UNFPA has been implementing various projects in Armenia. It was the first institution to raise the issue of sex-based selective abortions in Armenia, and in 2013 launched a large-scale campaign to address it.

Tsovinar Harutyunyan, executive director of the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) in Armenia, says that since 2013, the ratio of boys and girls in Armenia has declined by one point each year, but in 2018, on the opposite, it slightly increased and reached 100 girls per 111 boys.

“We are sorry to see the 2018 record”, she says.

The UNFPA Armenia Country Office notes that it takes a long time to get to the normal ratio. After all, people’s behavior should be changed by urging them not to resort to sex-based abortions.

According to Tsovinar Harutyunyan, this is usually the case in the countries where there are three main preconditions: significantly decreasing birthrate, developing technologies that can determine fetal sex, and preference to sons.

In 2013 Armenia came third after China, where 118 boys were born per 100 girls, and Azerbaijan, where the girl-boy ratio was 100-116. Numbers exceeding 110 have been observed in India, Nepal, Vietnam, Albania and Montenegro as well as in neighboring Georgia.

For example, in India there is a custom of giving a girl a dowry, which is an economic burden for parents. This is why people refuse to give birth to girls.

The issue of sex-related abortions is particularly acute in the Gegharkunik region of northern Armenia, where the numbers are almost on the same level as in India or other countries in the world leading with selective abortion numbers.

In Martuni Maternity Hospital, visited by women from almost all villages of Gegharkunik, only few girls are born. For example, 60 of the 106 children born here this January are boys, 46 are girls, while in February, there are 32 boys and 19 girls born.

During the previous two years, the organization led by Anahit Gevorgyan organized meetings with residents in different communities of the province, carried out awareness activities on the importance of a baby girl, birth balance and other topics.

“The daughter-in-law of one of my acquaintances is pregnant. They are expecting their third child. They found out that she is a girl. They came to me, very upset, but she said: “Anahit Jan, whatever happens, she must have it, it is God-given. How can I tell my daughter-in-law to take the baby out?” We have recorded results like this during our program,” she tells MediaLab.

According to the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), as a result of selective abortions, every year there are 1700 more boys born in Armenia, and 1500-2000 girls that aren’t born. According to UN forecasts, by 2060, 93,000 girls will not be born in Armenia. This number almost equals to the number of children born in our country during a three-year period.

“We lose the birth rate of about three-year period only because of the preference for a boy in our country,” Tsovinar Harutyunyan says.

Karine, a 27-year-old woman from Vayk, hid the ultrasound results about her third child from her family, telling them they would have a son.

“For 7 months I was greatly taken care of, received attention, good food, vitamins, but as soon as my daughter was born, everyone turned ice cold. My husband didn’t even come to take us home from Maternity hospital, and when we were at home and the baby was crying, my mother-in-law told me to ‘go and make your baby shut up’’ she tells MediaLab.

In 2017, in the framework of “Combating discrimination against fetal sex selection” project, International Center for Human Development (ICHD) carried out a study, according to which the basic arguments justifying the preference for boys include the following: “The boy is the one who continues the family lineage” (64%), “The boy is the heir of the property” (33%), “The boy is the defender of the homeland” (17%).

Ethnographer Aghasi Tadevosyan says that a more conservative part of Armenian society has traditionally favored boy children.

“In ancient Armenia people wanted to have a son based on economic reasons. Strictly based on having a workforce on the field, the birth of boy children was considered important because the more men there were in the family, the more hopeful for better life they would be. This approach dates way back,” the ethnographer explains.

He also cites common expressions in Armenia that apply to women who have a daughter: “You are lazy”, “You are like your mother”, “You did not manage to have a son”.

The ethnographer says that a woman who gives birth to a baby boy has had a guaranteed stability in the family. Meanwhile, the content and form of congratulations change when a girl is born: “It’s ok, the most important is that the child is healthy, the one who gave birth to a baby girl, can give birth to a baby boy too.”

The desire to have a son is so strong that at weddings, the bride symbolically holds a baby boy in order to have a son.

“There is a big family in Martuni where one of the two brothers has two daughters and the other has two sons. The wife of the brother who had girls said that during celebrations the family members toasted for the other brother’s wife, while she was never even mentioned. She said, she felt like she was not even the daughter-in-law of that family,” says Anahit Gevorgyan.

Times have changed, and ethnographer Aghasi Tadevosyan believes that such an approach, which has been mistakenly considered national, has no basis for existence today. The ethnographer says that he has noticed that his young students are educated and have humanistic values.

“Finding a solution to gender-based discrimination is very important in our society, and I think the best way to tackle this issue is the education system, the knowledge. We should change this through education, because it is an issue of society’s enlightenment, and enlightenment issues are solved through education,” Aghasi Tadevosyan says.

Illustration by Vahe Nersesyan

MediaLab.am